The doorknob is what got me. We had the same faux aged, fake bronze doorknobs with the Greek meander design on all the doors in our house. I was Carol Anne’s age when Poltergeist was released in 1982 and her brother’s age when I saw the movie for the first time. When Robbie struggles with the knob in that final, frantic escape sequence, the camera is at his eye level, my eye level — that scene is probably what scared me most at the time since it felt like it could be happening to me and my family. In fact, every door in all my friend’s and neighbor’s homes had the same door knobs. Every house in “Rancho Ponderosa” could have been every house in “Cuesta Verde” but the mass-produced and mass-installed hardware were not the only similarities. For a while, I honestly thought the movie took place in my neighborhood. I am fairly certain that this was the experience of every child who saw Poltergeist that grew up in Southern California in the late seventies and early eighties and why the movie has held up for us as long as it has, even for those who haven’t seen it in decades.

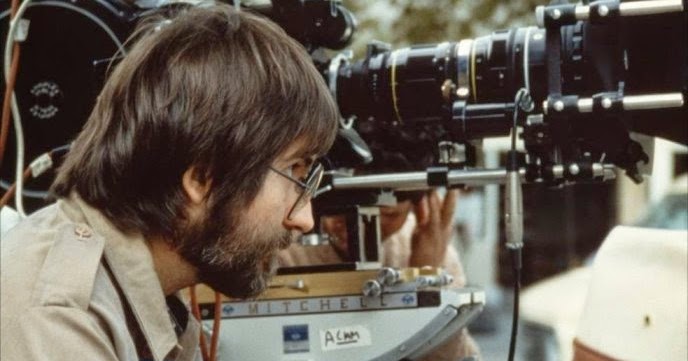

But aside from youthful terror nostalgia, director Tobe Hooper and Steven Spielberg’s contemporary suburban horror classic reminds viewers of a certain age of the anxious, giddy fiscal optimism and suppressed colonial guilt that accompanied the death rattle of the cultural revolution and the birth of the Trump Era.

Hooper died Sunday of natural causes at 74. In his honor, I decided to rewatch this great, underrated film that has been a touchstone for me and my generation.

I grew up in north San Diego County. Our housing development was the first of many sprawling, assembly-line neighborhoods that would swallow the farmland and wilderness that surrounded them. Our house was right on the edge so I could literally hop our backyard fence and explore the acres of arid chaparral that still dominated the landscape. It’s a little shocking to remember that the neighborhood kids and I forged bike paths, caught snakes and scorpions, and discovered ancient, rickety tree houses, some of them fifty feet in the air, and the concrete, stone, and brick foundations and chimneys of the homesteaders whose children had built them.

Occasionally, we’d also find fire rings old enough to encircle full-grown Manzanita shrubs with stones studded with the shells of marine creatures. Lucky kids even found mammoth teeth or stone arrowheads on occasion.

We also ran into camps; tiny shantytowns of plywood, cardboard, and sheets, empty during the day while their occupants picked flowers and fruit and groomed our yards. Though most of us had no idea of their function at the time, we could hear their music and see the lights from their fires at night. It was a strange set of circumstances and one I have yet to see depicted in cinema, though the symbolism of Poltergeist has come as close any film I have seen, besides maybe El Norte, to capturing coziness and dread of Southland suburbia in the eighties.

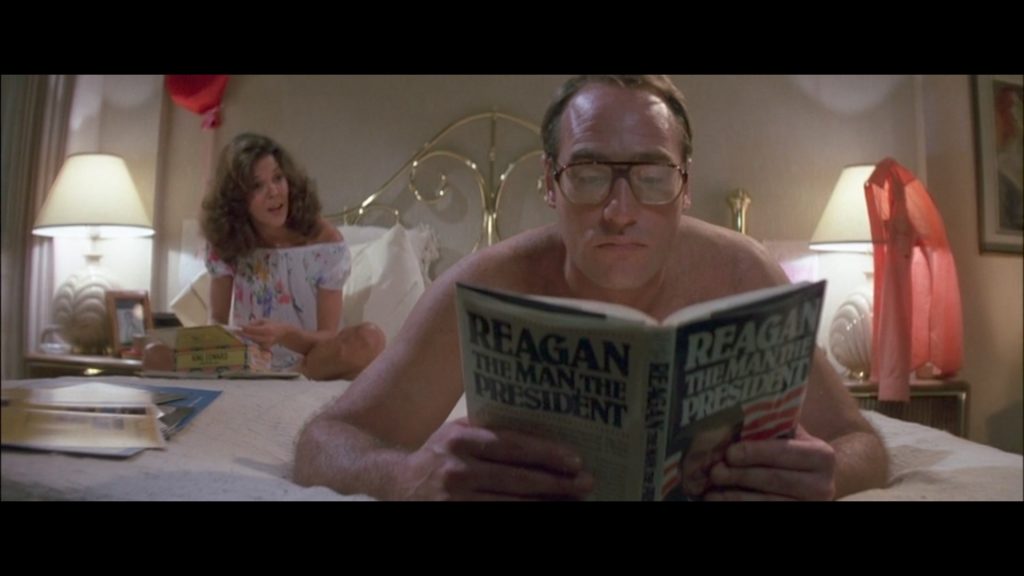

Imagine a movie marketed to the mainstream today with the scene of the parents giggling and flirting, chain-smoking joints in bed while the man of the house is simultaneously engrossed in a fawning Reagan biography. The mother only pauses briefly and unhurriedly to extinguish their roach when their seven-year-old walks into the room, frightened by the thunderstorm outside.

Imagine the outcry from the right as well as the left! Not that I am disparaging the message or anything so trite. It happened all the time and still does; no worse than a child witnessing their parents have a glass of wine. But again, would they let us see that now outside the arthouse? How about the older daughter’s interaction with the catcalling construction workers and the mother’s cheerful dismissal of the event? This was the freedom of the film industry shake up of the seventies attempting to reconcile itself with the commercial concerns and subsequent corporate takeover of the film industry that would come to define the next three decades.

Notice the change in tone of Mr. Freeling’s tequila binge scene in the lesser sequel, released just four years later. A demon actually enters his body through the bottle — a symptom of the ham fisted moralizing that has dominated American filmmaking since. Consider this with respect to the symbolism of the tree and the cemetery in the first film.

I’ve had nightmares about that tree, mostly as a child. “It knows I live here”. What better metaphor for the unconscious suspicion, even in a child, that one does not belong to the land they occupy, that the connection to one’s environment is forced and might dissolve at any moment. I first witnessed as a teenager the increasingly destructive and frequent wildfires that now threaten the fantasy of coastal California living.

I thought of that tree as I watched the increasing orange glow in the skies behind the hills. I watched the flames crest those hills like the spume of a hellish wave only to have them quashed by helicopters bearing water and four lane highways.

I thought again of that tree when I learned, along with the scientific community, that the Torrey Pine, an endangered Pleistocene holdover whose conservation had baffled environmentalists, could only germinate in the aftermath of fire. My tree dreams diminished to nothing as I grew up, but I recently had a dream about a small tornado in my backyard, the floor of which had filled with water.

I did not understand where that image had come from until I watched the movie again today, having learned about Hooper’s death this morning. My childhood home was structured nearly identically to that of the Freelings, minus the curved staircase. It was two stories with a shake shingle roof that sloped down to the garage door on the right and opened up to windows on the atrium, upstairs bedrooms and living room on the left. We even had the ridiculous carpeted bathrooms. We also suspected that the house had been built over a cemetery.

Let me first explain that I grew up in a relatively strict Catholic household. We lived with my grandmother who would tell us frightful stories about her experiences with ghosts and, us being good Catholics, we believed in the spirit world and the stories she told us of ghosts turning on lights and appliances, including the TV. Sometimes they even sat on her chest in the night, their demonic weight preventing her from struggling or screaming for help.

I later learned that she probably suffered from sleep paralysis since I would experience that terror myself later, but at the time, ghosts were real and they interfered in our lives on a regular basis. Since the house was fairly new, that meant that nobody had died in it and that must mean that we had disturbed sacred ground. Knowing, as we had learned in school, that Native Americans, Spanish, Mexicans, and Germans had occupied this land in succession before us, this seemed imminently plausible to my as yet non-lapsed Catholic mind. Poltergeist seemed to confirm my suspicions. I fully expected sufficient rain to produce a reverse cascade of exploding coffins, not realizing at the time that I was experiencing Colonial guilt.

I found out later from the grandmother of a friend who had lived in our town in the thirties that much of the land around us had been lived on, owned and worked by the descendants of Japanese immigrants, who had all been removed to camps during the war and whose property had subsequently been confiscated and sold to local whites. I had never heard this from anyone in town, but it did not surprise me.

Then there were the headstones.

All my life I had seen two white crosses on the side of the road that lead between our town and the adjoining town where our relatives lived. They were large and rested at the bottom of a bluff near a quarry and stream that eventually emptied into a nearby lagoon. Everyone knew of them but no one knew anything about them.

Once, when I was just out of high school, I stopped to get a closer look at them. They were larger than they looked from the road and made of stone, which confirmed what I had already known — that they had been there for decades and were not simple roadside shrines. I could not find any inscriptions. Two years ago I traveled back to my hometown for my twentieth high school reunion. On my way back into town I realized that the tract houses had expanded farther than I’d ever thought they would. The road between our towns had been widened and the headstones were still there… but on the other side of the road.

Hooper certainly deserves credit for his other great contribution to American cinema as well—the bloody and brilliant Texas Chainsaw Massacre. But that film, while thoroughly enjoyable and widely influential in certain circles, did not have the same wide audience and, for me, resonance that Poltergeist did. TCM was a satirical cartoon. The Freelings felt like a real family and they lived in a real place—not just any place, but my place and that was what made the movie so terrifying. Hooper did not accomplish much outside of these two masterworks, (most of his other films did poorly at the box office and weren’t well received by critics) but he is entitled to respect for making a nightmare of the American dream.

RIP Tobe Hooper

1943 – 2017

Chris Vena is an artist and photographer from San Diego County. In 2004, he moved to Seattle where he lived until moving to Istanbul to teach art in 2010. He returned to the US in late 2014 is now an instructor of painting and drawing at Northern Arizona University. In 2013, a violent police crackdown on peaceful protests in Istanbul’s Gezi park led to a nationwide uprising that would last throughout that summer. Chris’ current work is a reaction to that experience and similar resistance movements which have begun to emerge in the US, Arizona in particular. You can follow Vena on Instascam @venachris

For more Phoenix coverage that doesn’t suck, follow PHX SUX on Suckbook and that tweety website for Twits.

Read more from PHX SUX: